In February 2016, Youtube content creator Nostalgia Critic released a new video, titled “Where’s The Fair Use?,” in which he explained his recent troubles with the automated copyright system employed by Youtube, and how potentially destructive it can be to anyone who bases their livelihood on content shared via Google’s platform. The video soon gained traction on social media, quickly becoming the most popular publication on his (at the time already very much relevant) channel with over 1.5 million views. It also resulted in multiple follow-up videos by other influential Youtube personalities echoing his statements, as well as #WTFU campaign conducted primarily by their audience. Thus, for the next few days, the issue of Youtube’s copyright policy became the next big topic in Internet-related discourse.

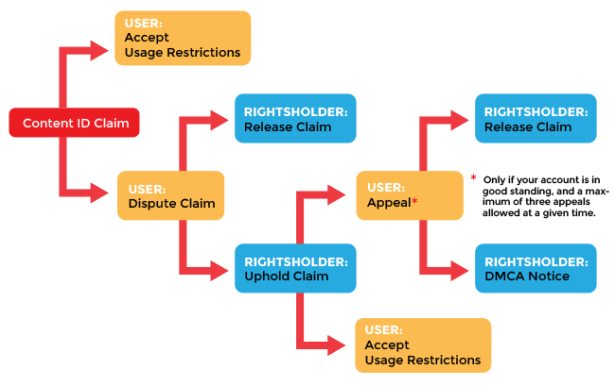

The Youtube copyright policy is a largely automated system, which in theory is designed to help the rightful owners of a copyrighted material claim their content from channels which use it without permission, thus breaking the law. The owners can, then, either upload a sample of their property for the system to detect and disable its illegal copies automatically, or claim ownership manually and either have the illegal video taken down, or keep it as it is, but have all the monetization redirected to the copyright owner.

(Image source: https://www.eff.org/issues/intellectual-property/guide-to-youtube-removals)

While the system sounds good on paper, its one major flaw is the human factor: it gives by design all the power to the copyright holders, either actual or alleged ones, trusting that they would use it appropriately and responsibly. This, however, is realistically not the case, as channels that produce videos that include any kind of audiovisual material – be it videos, music, or gameplay footage – receive takedown notifications from trigger-happy companies on a daily basis. The ease of issuing copyright strikes, coupled with Youtube’s “guilty until proven innocent” approach to content creators, lead to a very unstable environment for the latter – 3 takedown requests, legitimate or not, may result in permanent closure of an entire channel. It is, then, the creators’ burden to prove their innocence at every single occasion, while the ones requesting a takedown are not really held to any responsibility.

The key term to understanding the situation is the American doctrine of fair use, which, because Google is based in the US, applies to all Youtube content creators regardless of their nationality. In essence, the law permits a limited use of otherwise copyrighted material for “transformative” purposes such as commentary, criticism, parody, and education – thus effectively serving as the foundation for almost every single “informative” channel that builds their original work on top of recycled content produced by someone else. The copyright holders, however, seem to have very little regard for the law, abusing the system to earn a quick buck or, more maliciously, silence negative criticism of their products – very clearly falling under the fair use law. And while more known channels are capable of fighting such claims and bringing the videos back, for smaller ones they might mean the end of their Youtube career.

Nostalgia Critic’s problems described in the influential video have provoked the subsequent debate and activism two months ago, but the phenomenon itself is by no means recent. The most publicized case of this nature dates all the way back to October 2013 and the dispute between gaming pundit Totalbiscuit and an indie developer who used the same means to censor the criticism of their subpar work. The video describing the situation is once again the most popular piece of content on the respective channel, currently sitting at little under 5 million views. It points to the exact same issues that Nostalgia Critic et al. describe almost 3 years later, suggesting that not much, if anything, has changed during the time.

On the other side of today’s spectrum is a curious, fairly recent phenomenon of “reaction” personalities, a kind of meta-Youtubers. They tend to build their unexplainably popular acts around the idea of playing videos from other channels, often in their entirety, and filming themselves “react” in real time to said works – sometimes with as little as just facial expressions.

As playing the original video on the “reacter’s” channel effectively denies any revenue from the original creator, and the act of reacting is arguably hardly “transformatory” to the work itself, a strong argument could be made that these are the type of videos that would not not fall under the fair use doctrine. Thus, these channels should probably not be allowed to take advantage of other people’s work. Despite several prominent personalities’ attempts at raising awareness of the problem, however, successful copyright strikes against these channels are virtually unheard of. The cynical (and not necessarily untrue) explanation is that due to the fact that the abused side in this case are not big companies, but usually one-man creators. Hence, Youtube management has very little incentive to fight for their rights, as the massive popularity of reaction videos brings the service too much ad revenue to pass on.

The current situation is perhaps best summed up by paraphrasing Drew Carey’s famous one-liner from Whose Line Is It Anyway?: The rules are made up, and the law doesn’t matter. Whichever way the misuse of copyright goes, however, it always seems to hurt the most the passion projects of small channels that helped build the community from the ground up when the platform first emerged. This is, then, not simply a sad state of affairs in and of itself, but also as relevant of a topic to the concept of digital culture as it can possibly get.

As there is much more to the issue than just the fair use dilemma, in the next posts the project will explore more in-depth the puzzling sphere of Youtube’s copyright policies, their basis in US law, where they have historically succeeded and failed, and what their future might bring.

Update: Shortly after the post was published, Youtube announced a much welcome change to how copyright infringment claims will be handled in the future. Instead of transferring all the revenue to the claimant immeidately, it will now keep the video monetized, but without actually paying either side untill the claim is resolved – thus enforcing a layer of protection for channels who might have been hit with an unlawful strike.